What are the Rules For?

A lot

Way back in 2003, Vincent Baker (of powered by the apocalypse fame) wrote

So you’re sitting at the table and one player says, “[let’s imagine that] an orc jumps out of the underbrush!”

What has to happen before the group agrees that, indeed, an orc jumps out of the underbrush?

1. Sometimes, not much at all. The right participant said it, at an appropriate moment, and everybody else just incorporates it smoothly into their imaginary picture of the situation. […]

2. Sometimes, a little bit more. “Really? An orc?” “Yeppers.” “Huh, an orc. Well, okay.” […]

3. Sometimes, mechanics. “An orc? Only if you make your having-an-orc-show-up roll. Throw down!” “Rawk! 57!” “Dude, orc it is!” […]

4. And sometimes, lots of mechanics and negotiation. Debate the likelihood of a lone orc in the underbrush way out here, make a having-an-orc-show-up roll, a having-an-orc-hide-in-the-underbrush roll, a having-the-orc-jump-out roll, argue about the modifiers for each of the rolls, get into a philosophical thing about the rules’ modeling of orc-jump-out likelihood... all to establish one little thing. […]

Mechanics might model the stuff of the game world, that’s another topic, but they don’t exist to do so. They exist to ease and constrain real-world social negotiation between the players at the table. That’s their sole and crucial function.

Emphasis mine. Similarly, Jared Sinclair wrote rules elide:

To say that rules elide is to say that they do nothing else. That they cannot do anything else. Rules do not themselves create or conjure or elicit or inspire or invoke or incite—they only negate.

I’m here to argue the opposite, more or less.

In my view, games are about making informed, impactful choices. The game system:

Can generate the choices

Can resolve the impact of a choice

Can the define the goal

That’s just on the game-side. The rules can also simulate (which helps in world-building and indirectly helps generate problems and resolutions), and enforce (or incentivize) a style or tone (like how Ten Candles directly tells players to keep the Tragic Horror tone in mind).

Generation

I think a good example is OSE's combat system. In typical combats, we decide:

Who to attack

What to wear to battle

Where to position

When to spend spell slots and consumables like potions and scrolls

These choices are immediately and obviously impactful, and winning combat directly results in XP (the goal), and indirectly results in more XP by removing the guardians between you and treasure (the goal).

These choices are generated by the system. OSE includes heaps of monsters to fight against, and tables for generating encounters and treasure. A GM can follow the rules of dungeon generation, and that will generate combats which in turn generate choices for the players that the system also resolves.

Other good examples of places where the system is generating the choices are…

How do I equip my character? The system includes equipment lists and magical item lists, weapons have trade-offs, armor has trade-offs, and the encumbrance, money, and class systems work together to limit options.

How do I spend my dungeon adventuring turn? Should I search the walls, listen at the door, stand guard, try to pick the lock, etc. This feels similar to playing a worker placement game.

Which spells do I prepare? The game presents a big menu of spells as options to learn, and then you have to pick a subset to prepare at the outset of an adventuring day.

When do I spend my spell slots?

What race/class do I play?

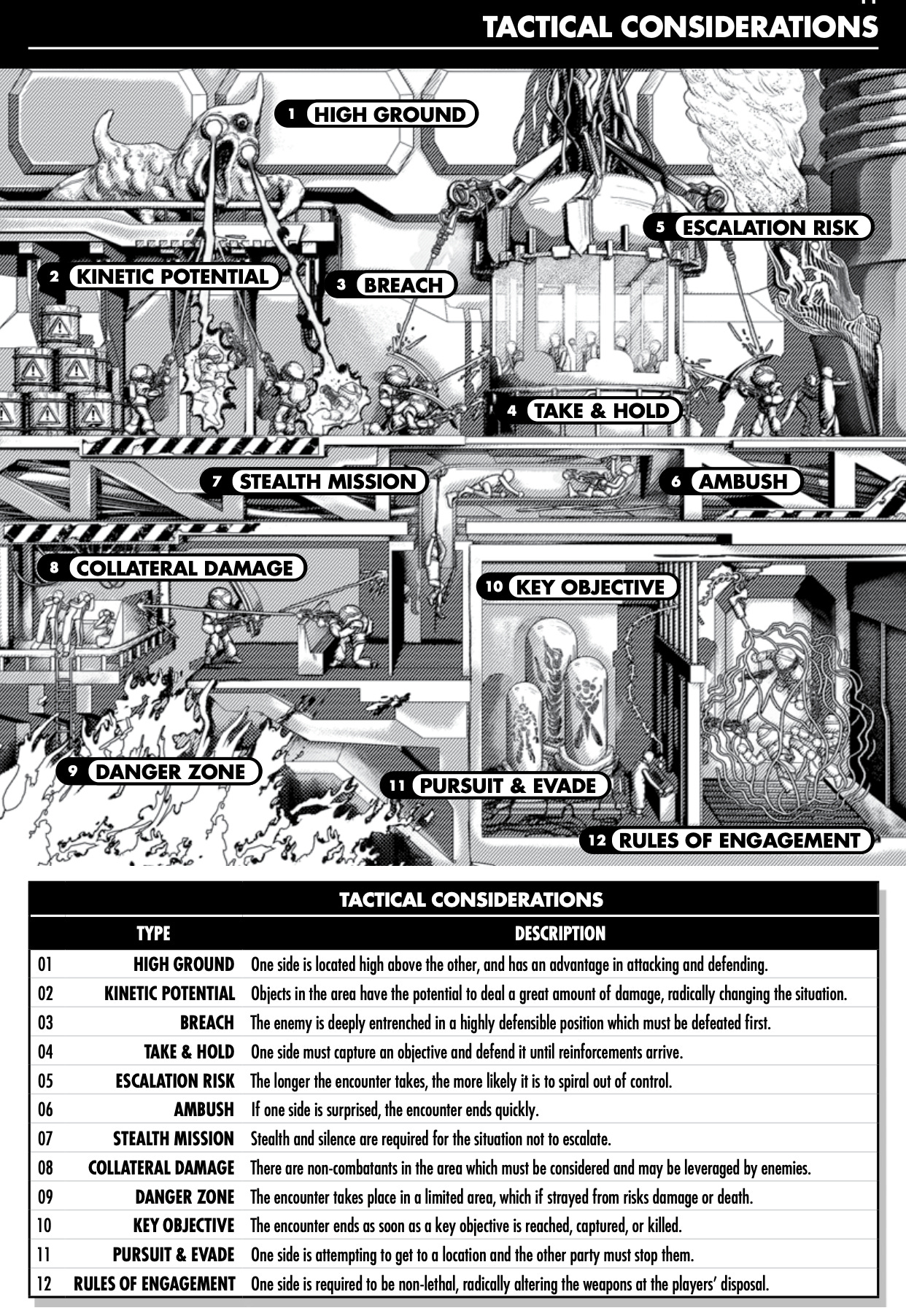

Sometimes, the generation is less direct. OSE, for example, does not generate dungeons for you, but it does have guidance for the GM to do so. Similarly, Electric Basionland and Worlds Without Number both come with heaps of GM guidance and spark tables to assist the GM in creating choices for the players (rather than the GM having to create the choices whole-cloth). Another good example here is Mothership’s TOMBS framework (Transgression, Omens, Manifestation, Banishment, and Slumber) and the Tactical Considerations table:

Resolution

Other times, the choice has to be directly generated by the GM, but the game system will help you resolve what happens. I think great examples here are mechanics for climbing or lock-picking. The GM has to put a wall to climb or a lock to pick in the scenario (which is part of level design), but when the players elect to engage with them, the system defines how it works (rather than asking the GM to invent it).

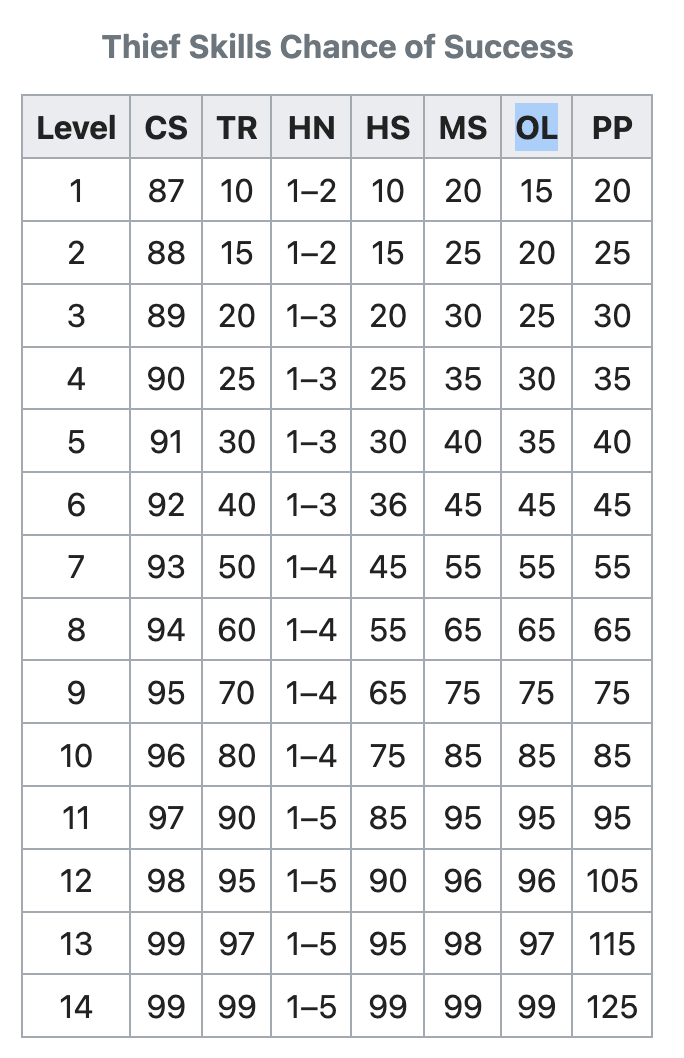

There’s a pretty wide spectrum of lifting that the system can do here. Strong assistance looks like the lock-picking mechanics from BX:

So the game system directly tells the GM (and player) the chance that a Thief can pick a lock, and directly tells them how this changes as they level up. Weak assistance looks like Knave 2e

These sorts of games usually provide a universal system (The GM picks a target, the player rolls a dice and adds modifiers) and some guidance around what the modifiers might be. Note how Knave asks the GM to do a lot more lifting to resolve the choice than the BX example: the GM has to figure out what the target number is, figure out which stat applies, and figure out how many +/-5s to apply. The GM has so much leeway here that it’s really similar to the system telling the GM to pick an X-in-6 or raw probability.

Other examples include:

Social situations. The GM has to create the situation, but the reaction roll/diplomacy check/etc helps resolve it.

Traps. The GM has to create and place the trap, but characters often have some sort of trap-breaking skill.

Searching for Hidden Doors. Same idea has traps - there’s often some sort of search roll.

Out of Scope

Tons of the decisions made by players will be created whole-cloth by the GM, and then also resolved entirely by GM fiat. The prototypical example here is moral dilemmas. The GM might create (whole-cloth) a situation where the players have to choose between saving their friend or party member or a lot of innocent strangers, and then the GM has to resolve the impact of that choice whole-cloth.

The motivation for this post was someone on reddit asking are OSR games good for the Magical Girls genre? OSR games are neither going to help generate or resolve the sort of interesting choices that are representative of the Magical Girls genre (so the GM is unsupported), and instead will generate lots of choices that get in the way of playing a Magical Girls game (it generates choices about equipment and dungeon turns which would distract from Magical Girls themes).

I think that if the bulk of the choices in your game aren’t generated (or assisted) by the game system, that’s a red flag. If the bulk of the resolution isn’t facilitated by the game system, that’s a red flag. If the system is generating choices that distract from the focus, that’s a red flag. If the system is resolving choices in a way that is incongruent with the genre, that’s a red flag.

Conclusion

So that would be my rebuttal to Vincent Baker, were I to ever get to talk to him. Mechanics do ease and constrain real-world social negotiation, but that’s not all they do. They also create a game - one where players are making informed and impactful choices. The same way that players can spend time analyzing chess moves or the best way to play a hand in Magic the Gathering, you can spend time analyzing how to position your team in a TTRPG fight, or whether you could have predicted this was an unfavorable fight from the start and should have fled. You can spend time figuring out if it’s better to carry a bow that has +1 to hit, or +1 to damage.

I totally get that some players aren’t interested in this part of the hobby, but it’s there! Some games have more of it (D&D 3.5e and 4e emphasize it more than 0e, for example), but it’s still there.

Great post, and after rereading it for a second time, I was wondering if I could prod your mind with regards to the concept of tactical infinity and how it might affect the choices players can make in combat.

Let us take, for example, the quite straightforward combat system of BX. Now let's say a player wants to do something that is not in the rules, e.g., called shots, grappling. Now, a GM could do one of two things. He could (a.) refer the player back to the rules ("You want to grapple the orc? Well, grappling is not possible in this system, so we handle it like a normal melee") or (b.) he can make up a ruling ("Well you are stronger then the orc, so a 4-in-6 chance that you will be able to pin him down").

Both strategies of handling these out of rules actions can have their implications on the choices the players will make afterwards. Strategy A will bring the focus back to the rules of the game and force players to make decisions within that context. E.g., if you want to beat the orcs, you got to overcome them through clever planning. Strategy B will probably make your players try more creative solutions to circumvent the combat system.

What is your view on this?

Some of the best sessions, high player interactions, high interest in keeping an energetic game play flowing, comes from finding ways to defeat the rules.

The rules are necessary for this to happen but should not ever be absolutes..